‘Tech neck’: Is your device causing you to get neck pain?

It saddens and scares me to understand how the excessive and unnecessary use of digital technology is harming the healthy functioning of our fragile nervous systems. We’re caught in a rapidly progressive whirlwind of commercialised digital chaos, and we’ve sadly (and almost innocently) become addicted to using smart devices.

I’m noticing an alarming amount of young people who are coming to see me for joint and muscle concerns that I wouldn’t necessarily expect to see in people who are under the age of, say, 30.

Also, I’m finding that young people are starting to see me more and more for random neck symptoms and signs that mimic people who’ve suffered a physical injury (such as a whiplash injury or a mild head trauma) which isn’t good.

Our inappropriate (or unnecessary) use of digital technology might be responsible for causing a new, modern-day clinical syndrome called ‘tech neck’.1

You might know other common names for ‘Tech Neck’, too, such as: ‘Computer neck pain’, ‘Postural strain’, ‘Monitor neck pain’, or ‘Screen neck pain’.

‘Tech neck’ syndrome can give people many different muscle and joint concerns, such as:

- Neck pain.

- Shoulder girdle pain.

- Upper back pain.

- ‘Pins and needles’, tingling or numbness sensations especially in the upper limbs.

- Headaches1,2,3

People get ‘tech neck’ posture when they repeatedly slouch their heads forward to use their smart devices. Also, people who spend many unnecessary hours a day using a handheld smart device increase their risk of getting a lot of bad changes to their spine structures (which include ligaments, tendons, and bones).1

People who regularly adopt ‘tech neck’ posture ‘switch off’ their brains’ ability to ‘talk’ to their neck structures, properly. Your brain relies on getting constant positive information from your body movements (which is called somatosensory feedback) to help it stay ‘switched on’. Unfortunately, if people keep doing a ‘tech neck’ posture and they don’t maintain healthy neck movement habits, their brains start to get lazy and learn bad body movement and posture behaviours.3,4 Therefore, people can get early neck (or cervical spine) degeneration issues if they keep doing repetitive poor body movement habits (or ‘tech neck’ posture).1

The process of your nervous system ‘learning’ how to do something new (whether it’s good or bad) is called, neuroplasticity.

So, is someone who keeps doing a ‘tech neck’ posture an example of good neuroplasticity or bad neuroplasticity for their body’s muscle and joint function?

When you use a smart device, you’re most likely to get ‘tech neck’ syndrome when you do a combination of six habits:2,3,5-7

- You have your head/chin tilted down by 30 degrees or more.

- You sit, as opposed to stand.

- You hold and use a smart device with one hand, only.

- You write/send a minimum of 6 text messages a day.

- You don’t support your arm/s on something when you’re using a smart device.

- You use a smart device for a minimum of 2-hours a day.

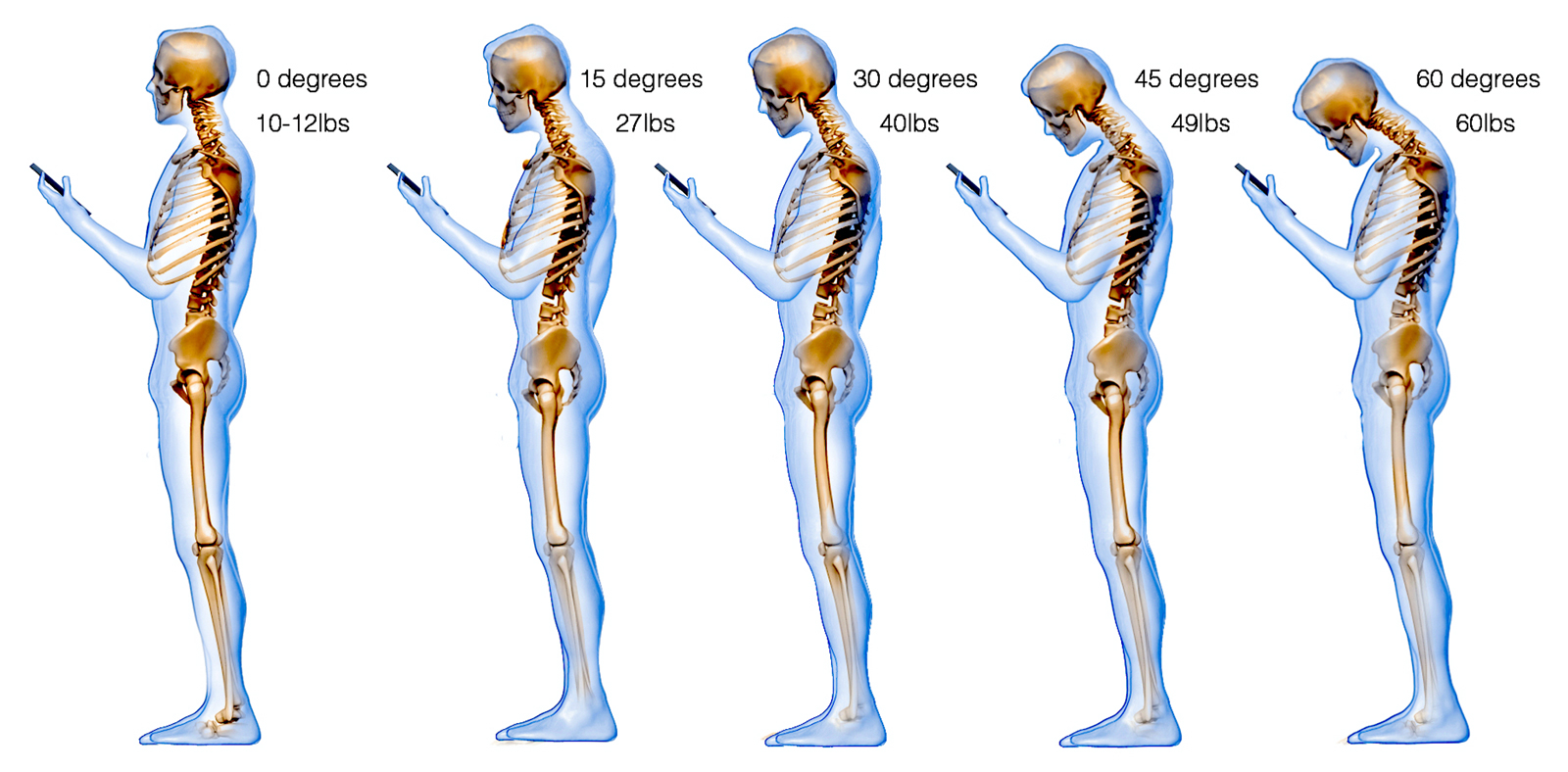

Moreover, people put an extra 18 kilograms of mechanical (or gravitational) stress on their neck structures when they tilt their head down by 30 degrees (or more) to look at the screens of their smart devices (image 1).6,7

However, some scientists8,9 have found that ‘tech neck’ doesn’t necessarily cause people to get neck pain which is interesting because it completely opposes what many people think about ‘tech neck’ side effects.

So, is ‘tech neck’ really that bad for our bodies if it doesn’t always cause us to get neck pain?

Overall, my answer is, “Yes” and this is my reasoning:

Our brains use special, invisible mapping systems to help us familiarise ourselves with our environments and hence warn us about potential stressful or dangerous stimuli. There are two main invisible maps that our brains use to alert us about getting hurt: our retinotopic (or seeing/visual) map, and our tonotopic (or hearing) map. However, I’ll keep things simple and from now on, I’ll refer to these maps as our brains’ ‘stress radar’.10-12

The process of us feeling worried, scared, stressed, or threatened is called our body’s ‘flight and fight’ response – that is, if we see or hear something that feels like it could hurt us, we either quickly decide to run away (or ‘flight’) or stay to protect ourselves (or ‘fight’).

Your ‘stress radar’ warns you about the possibility of you experiencing danger – it tells you about random surrounding movements, sounds and colour changes.11

For example, pretend that it’s garbage night and you need to take your wheely bin out to the front of your house. You don’t bother to turn on your front light because you think to yourself, “I know and trust my neighbourhood. I’ve got this”.

You casually wheel your bin out to the road and as you park it on the curb, you hear a twig snap behind you. You startle. Your ‘stress radar’ triggers your body’s ‘flight and fight’ response.

Your ‘stress radar’ detects that there’s something moving to the left of your body. Your brain quickly tells your head and eyes to turn left and look at the unknown object that’s moving closer you.

As you’re getting ready to ‘flight’ (or run away), your brain quickly recognises that it’s nothing other than your neighbour’s friendly pet goat, Allen.

Your ‘rational’ brain kicks in and it quickly ‘switches off’ your ‘flight and fight’ response – your ‘rational’ brain says to you, “It’s all good – it’s just a goat. There’s nothing to worry about.” You breathe a deep sigh of relief, and before you go back inside, you wish Allen a lovely evening.

Our eyes are connected to our spine muscles.13, 14

It’s very important that our eyes and head work together (as a team) because it helps our vision (or visual acuity) to stay sharp and focused.11 Also, scientists have discovered that our neck muscles tense when we think (or anticipate) that something’s going to move.15

So, wait a minute, are you saying that my neck muscles automatically tighten when I even think about scrolling my social media pages up or down on my smart device? Yes, that’s exactly what I’m saying – your neck muscles tense up whenever you think about scrolling (or physically scroll through) content on your smart device’s screen and there’s nothing that you can do about it. It’s a primitive, natural, hard wired reflex that’s part of our neurophysiology. People who spend excessive amounts of time using their smartphones abuse this natural neurologic reflex and consequently, they become victims of ‘tech neck’.

Therefore, your body’s ‘stress radar’ is triggered when we:

- See something move quickly.

- Hear something that could mean danger.

- See something change colour.

- Predict that something’s going to move.11,12,15,16

Also, did you know that your brain releases dopamine whenever your ‘stress radar’ is activated?

Dopamine is our natural pleasure and reward hormone that helps us to feel good when something (supposedly) positive happens to our bodies. It’s a hormone that helps us to feel addicted to doing healthy things, such as: exercising, socialising with our friends, eating nutritious food, and helping other people. However, sometimes, if our ‘stress radar’ keeps getting unnecessarily ‘switched on’, our bodies can make too much dopamine and we risk becoming addicted to learning bad health habits, such as: alcoholism, taking harmful drugs, or gambling too much.11

So, can you think of a commonly used, handheld digital device that’s been designed to make us: see things that move quickly, anticipate that something’s going to move, see rapidly changing colours, and feel good when we hear an alert tone? A smartphone.

Moreover, people who repeatedly do a ‘tech neck’ posture can indirectly ‘switch off’ parts of their brain that are responsible for controlling their:

- Balance and coordination.

- Voluntary muscle movements.

- Appropriate contextualised emotions.

- Sleep function.5,17,18

Unfortunately, people who regularly trigger their ‘stress radar’ by doing excessive and unnecessary stressful eye movements (such as looking at their smartphones too close to their faces) and do a regular ‘tech neck’ posture risk themselves getting bad nervous system conditions, such as: dystonia (or severe and sustained muscle contractions), and Parkinson’s disease.12,18,19

A summary: how do you know if your nervous system could be a victim of ‘tech neck’ syndrome?

Overall, yes, your digital device could be causing you to get neck pain but sometimes, you don’t have to have neck pain to be a victim of, ‘tech neck’ syndrome.

You could have ‘tech neck’ complications if you get a combination of any of the following symptoms and/or signs:

- You get pain and/or headaches.

- You get ‘pins and needles’, tingling or numbness sensations especially in the upper limbs, hands and/or fingers.

- You get distracted easily.

- You tend to be sensitive to sensory stimuli, such as: sound, light, and touch.

- You get motion sickness (which includes you not being able to read whilst you’re travelling on transport without you feeling sick).

- You tend to overreact to common or trivial situations.

- You tend to have impulsive or aggressive behaviour.

- You get angry easily or have random emotional outbursts.

- You have digestive problems and food sensitivities.

- You startle or get scared easily.

- You have balance and coordination problems.

- You get random muscle jerks (or spasms) and can have difficulty controlling your muscle movements.

- You have obsessive compulsive behavioural tendencies.

- You have a regular and intense urge to clear your throat or move a group of muscles to make you feel comfortable, better, or relaxed.

- You get nervous easily and have a restless mind.

- You regularly get neck muscle and/or back muscle tightness.

- Your back muscles tire easily when you stand or walk.

- Your voice appears to be getting softer.

- You have unexplained constipation.1,2,3,17,20

References

- David D, Giannini C, Chiarelli F, Mohn A. Text Neck Syndrome in Children and Adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb 7;18(4):1565.

- Eitivipart AC, Viriyarojanakul S, Redhead L. Musculoskeletal disorder and pain associated with smartphone use: A systematic review of biomechanical evidence. Hong Kong Physiother J. 2018 Dec;38(2):77-90.

- Gustafsson E, Thomée S, Grimby-Ekman A, Hagberg M. Texting on mobile phones and musculoskeletal disorders in young adults: A five-year cohort study. Appl Ergon. 2017 Jan;58:208-214.

- Kingett M, Holt K, Niazi IK, Nedergaard RW, Lee M, Haavik H. Increased Voluntary Activation of the Elbow Flexors Following a Single Session of Spinal Manipulation in a Subclinical Neck Pain Population. Brain Sci. 2019 Jun 12;9(6):136.

- Wah SW, Chatchawan U, Chatprem T, Puntumetakul R. Prevalence of Static Balance Impairment and Associated Factors of University Student Smartphone Users with Subclinical Neck Pain: Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Aug 28;19(17):10723.

- Han H, Lee S, Shin G. Naturalistic data collection of head posture during smartphone use. Ergonomics. 2019 Mar;62(3):444-448.

- Hansraj KK. Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head. Surg Technol Int. 2014 Nov;25:277-9.

- Correia IMT, Ferreira AS, Fernandez J, Reis FJJ, Nogueira LAC, Meziat-Filho N. Association Between Text Neck and Neck Pain in Adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021 May 1;46(9):571-578.

- Damasceno GM, Ferreira AS, Nogueira LAC, Reis FJJ, Andrade ICS, Meziat-Filho N. Text neck and neck pain in 18-21-year-old young adults. Eur Spine J. 2018 Jun;27(6):1249-1254.

- Kandler K, Clause A, Noh J. Tonotopic reorganization of developing auditory brainstem circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2009 Jun;12(6):711-7.

- Hikosaka, O., Kawagoe, R. & Takikawa, Y. Role of the basal ganglia in the control of purposive saccadic eye movements. Physiol. Rev. July 2000;80(3):953-978.

- Nambu, A. Somatotopic organization of the primate Basal Ganglia. Front Neuroanat. 2011 Apr 20;5:26.

- Bexander, C., Mellor, R., and Hodges, P. Effect of gaze direction on neck muscle activity during cervical rotation. Exp Brain Res. 2005 Dec;167(3):422-32.

- Petit L, Beauchamp MS. Neural basis of visually guided head movements studied with fMRI. J Neurophysiol. 2003 May;89(5):2516-27.

- Goonetilleke SC, Katz L, Wood DK, Gu C, Huk AC, Corneil BD. Cross-species comparison of anticipatory and stimulus-driven neck muscle activity well before saccadic gaze shifts in humans and nonhuman primates. J Neurophysiol. 2015 Aug;114(2):902-13.

- Schneider KA, Kastner S. Visual responses of the human superior colliculus: a high-resolution functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurophysiol. 2005 Oct;94(4):2491-503.

- Joel Brandon Brock, Samuel Yanuck, Michael Pierce, Michael Powell, Steven Geanopulos, Steven Noseworthy, Datis Kharrazian, Chris Turnpaugh, Albert Comey, and Glen Zielinski. The potential impact of various physiological mechanisms on outcomes in TBI, MTBI, concussion and PPCS. Funct Neurol Rehabil Ergon 2013;3(2-3).

- Pong, M., Horn, K., and Gibson, A. Pathways for control of face and neck musculature by the basal ganglia and cerebellum. Brain Res Rev. 2008 Aug;58(2):249-64.

- Mc Govern EM, Killian O, Narasimham S, Quinlivan B, Butler JB, Beck R, Beiser I, Williams LW, Killeen RP, Farrell M, O’Riordan S, Reilly RB, Hutchinson M. Disrupted superior collicular activity may reveal cervical dystonia disease pathomechanisms. Sci Rep. 2017 Dec 1;7(1):16753.

- Chen Z, Li G, Liu J. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: Implications for pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurobiol Dis. 2020 Feb;134:10470

Image 1. A picture showing how a person’s worsening ‘tech neck’ posture can force extra and unnecessary mechanical (or gravitational) stress on their vulnerable spine structures.7 Therefore, you could put a staggering 27 kilograms of extra mechanical stress on your neck structures if you tilt your head down by 60 degrees to look at your smart device’s screen.

Recent Comments